No future for coal’ is old news – no future gas either

Posted by admin on 11/06/2014 at 5:03 amSustainability is mercurial, an ever retreating horizon. Just when you think you’ve arrived, you find it’s moved on, and yet again you have to rethink your strategy, your choices, your designs and specifications. And you have to keep moving on.

At this point in human history, sustainability in not a known destination. It is a process, a journey. A journey begins with the first step, and it’s important to recognise that our society – and the building industry within it – is a giant resource-hungry beast, with all the inertia of a super-tanker at full speed. Changing direction is not instantaneous, and can be jerky, especially with the poor long term political vision we suffer. But change is certain.

Drivers for change have been with us since time began. Some drivers are aspirational, like the invention of brick veneer: a house that looks like a real brick house but is much faster and cheaper to build. Others spring from necessity, such as the trend toward smaller lots: there just isn’t enough land to maintain the quarter acre dream.

Some drivers come from heeding the warnings of science, and the political imperatives that (should) follow them. BASIX in NSW is one such, as is BCA 6 star in other states. The notion of ‘journey’ can be seen clearly: in 1998, from a base of zero, the NSW Energy Smart Homes Policy was Australia’s toe-in-the-water for thermal performance regulation, with a minimum compliance level of 3.5 stars. It was introduced in response to more than twenty years of warnings about climate change, and the electricity grid’s regular failures to cope with demand. The sky did not fall – but then, 3.5 stars is a doddle for a blind man on a tightrope.

The journey continued when BASIX arrived with its slightly higher 4.5 star (average equivalent) standard, which scared a lot of builders. Surely the sky would fall. It was supposed to introduce orientation-specific designs, and rid us of the bane of greenhouse emissions and peak load management: air conditioning. It did neither. The blind man danced a jig on the tightrope and not much changed.

Other states later adopted the BCA’s 5 and then 6 stars, although with its slightly less stringent methodology. In 2007 three federal ministers, convinced the sky would fall, launched an unprecedented attack on the Australian Building Codes Board over the “outrageous” introduction of thermal performance into the BCA. Ministers Macfarlane, Campbell and McDonald said that this would mean: “the death of the iconic Queenslander”. As it happens, Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen was already dead. That same year I won a national design award for a contemporary tropo Queenslander that was rated at 6.5 stars. The sky once again did not fall, in fact the blind man learned to dance a jig standing on his hands on that tightrope.

Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen in full flight, opposing the creation of the Great barrier Reef Marine Park. Photo – Brisbane Times

But all of that is only about thermal performance of the building envelope, which is just one tile in the broad and growing mosaic of sustainability. Which brings me to the topic of stoves.

We have thought for the last twenty years that gas is a generational stepping stone to wean us off coal, with emissions believed to be about 30% of black coal. Turns out that’s a bit wrong, because the rogue emissions at the well-head are not counted, nor are leaks. Given unburnt gas’s massive greenhouse impact, real emissions may be more than 50% of coal.

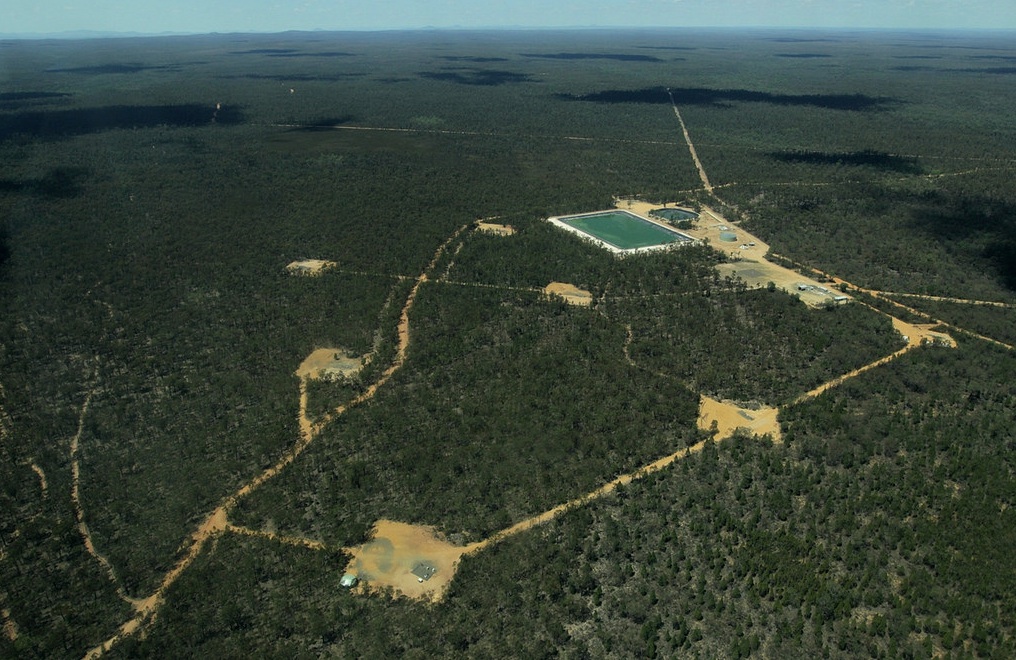

Then the CSG juggernaut rolled into our forests and farmlands, and a whole new truckload of risk and damage factors entered the equation.

CSG exploration wells in the Pilliga Scrub, NSW. Photo – Lock The Gate Alliance.

All fossil fuels now have so many known and suspected negatives, that the ever-advancing sustainability movement has dropped them like the smelly old fossils they are. Gas is now off the agenda for any project pursuing the most sustainable practice. Hot water, cooking, the lot – but replaced with what?

The drivers for change? Technology and economics have moved on dramatically in the last couple of years. Solar power is now so cheap, and heat pumps and induction cooking so efficient, it actually makes more economic sense to get back to the old 60’s saying “Live better electrically”. There are various ways of setting this up, with or without generous feed-in tariffs.

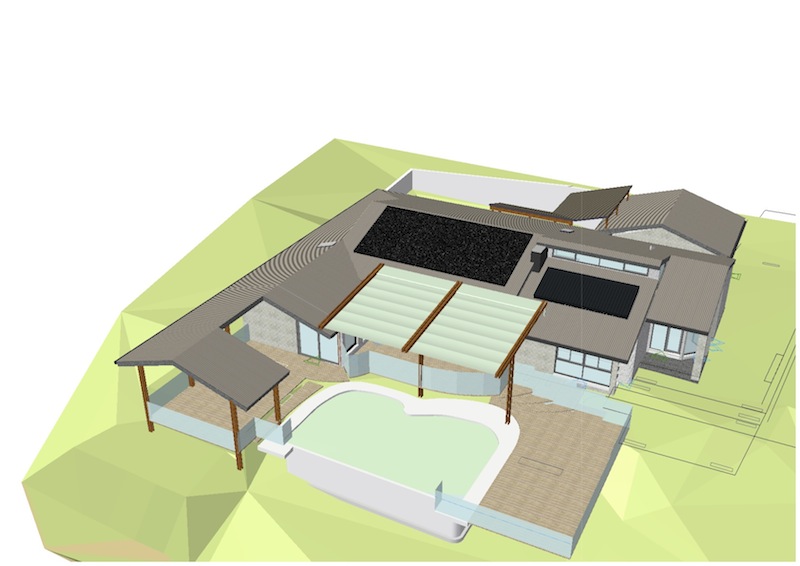

The best method is to align most of the building’s loads with the peak solar (PV) productive hours. For example, an efficient heat pump, with a coefficient of performance of 4 or better (CoP = units of heat produced for every unit of energy consumed), can heat a 315L tank in a few hours, in winter. This is stored for later use either as potable hot water, or for hydronic heating, or both. Hydronic heating has no equal in the pleasant radiant heat it imparts to occupants. The cost of a combination hot water and hydronic heat pump system has almost halved by using PV powered heat pumps instead of solar-gas systems. And they can achieve zero emissions, with zero running costs. Getting customers to see those benefits is not hard!

Model of a PV powered house with roof mounted heat pumps for hot water and hydronic heating. The twin heat pumps are located behind the screen enclosure that looks like a chimney, between the two PV arrays. This project is nearing completion in north-west Sydney. Image – Envirotecture

Cooking with induction cooktops requires a lot less power than the old resistive elements, although ovens still use them, albeit for very few hours in the course of a year. The trick with cooking, which is mostly done in the evenings, is to store some of that clean solar energy harvested during the day. Energy offset management systems (clunky title, but hints there’s more to it than just ‘batteries’) allow the PV system to ferret away excess power, rather than exporting to the grid for a pittance. This is stored and managed by intelligent systems that allow it to be used in the home as required later, before anything is imported from the grid.

Other savings include the deletion of any gas connection, pipework and gasfitting labour charges. In the case of hot water, tanks and heat pump locations are very flexible, and the plumbing between them simple and inexpensive. Never mind the blind man, the tightrope has joined in the dancing!

This shift will reduce domestic demand for gas of all kinds, both “natural” (which it isn’t) and “unconventional” (fracked from coal seams). The media beat up about a looming gas shortage, in fact driven by the rush to export gas for higher prices, will cease to be an issue – they can do with their gas what they like – we don’t need it! Listen now for the cries about the sky falling.

Further info…

Ross Gittins

Ross Gittins, Economics Editor at The Sydney Morning Herald, has this to say about the “gas shortage”: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/industrys-coal-seam-gas-campaign-is-a-con-20131008-2v63m.html

This blog is the text of an article written for the Master Builders Association of Australia 2014 national journal BuildIT, published by Crowther Blayne.

Sustainable House Design

We will help you create a family home that works well, feels good, is kind to the environment, culturally appropriate and reduces your energy and running costs.

Read MoreSustainable Commercial Buildings

We design your building to help reduce your operating costs, optimize the life cycle of your building, increase your property value and increase employee productivity.

Read MoreWorking with Envirotecture

We design beautiful, sustainable buildings that work for you, your family or your business. Full range of building design, consulting and training services.

Read More